[ad_1]

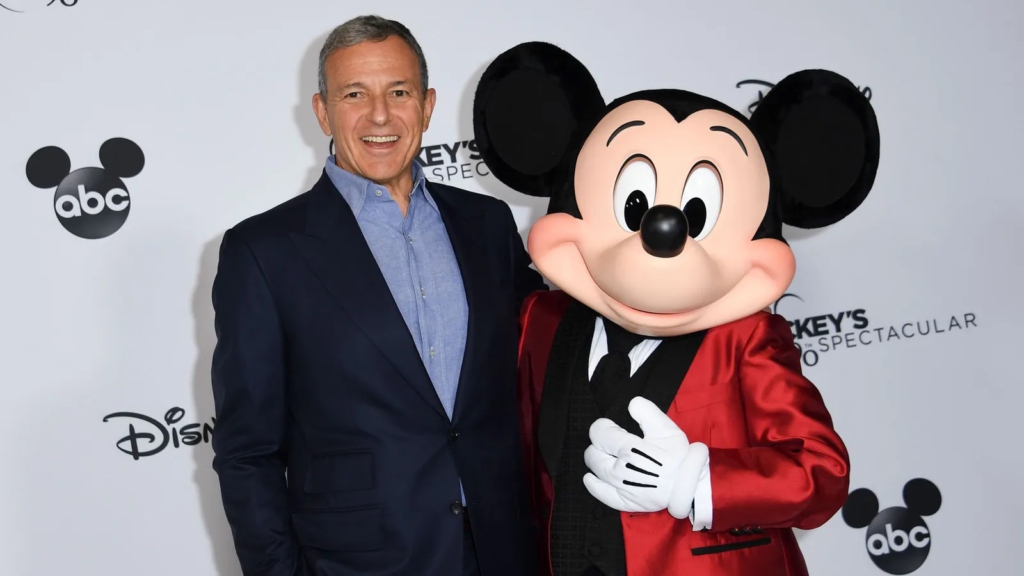

In January, Disney employees received a memo from CEO Bob Iger. Like other entertainment conglomerates, the media giant had been operating a hybrid-working policy, in which teams were allowed to work remotely twice a week.

However, Iger explained in the memo, the company was now reversing course, mandating a four-day return to office beginning in March.

“As you’ve heard me say many times, creativity is the heart and soul of who we are and what we do at Disney,” he wrote. “And in a creative business like ours, nothing can replace the ability to connect, observe and create with peers that comes from being physically together, nor the opportunity to grow professionally by learning from leaders and mentors.”

Disney isn’t the only major corporation pulling back on workplace flexibility. Across sectors, companies including Starbucks, Twitter and auditing firm KPMG are mandating more in-person days, or even a return to full-time office working patterns.

According to a January 2023 survey of 1,806 US workers by recruitment-agency Monster, while half of employers believe giving employees flexible schedules has worked well, a third who planned to adopt a virtual or hybrid model have changed their minds from a year ago.

While CEOs cite the need for in-person collaboration, camaraderie and mentorship as reasons for returning to the office, studies show that what many employees value most is flexible work. The arrangement has reduced worker burnout, boosted work-life balance and even, in many cases, improved professional performance.

This means that there is, indeed, a mismatch between what employers want and what their workers want – yet bosses are forging on with bringing their employees back in.

The return to more in-person settings is a significant development in the changing world of work, especially given workers have had the upper hand when it comes to bargaining for flexibility during the hiring crisis.

But as economic uncertainty looms, and companies axe jobs on a wide scale, the power dynamic is swinging back towards employers: many may be using the downturn as an opportunity to enforce or overhaul their working practices. For affected workers, fears of recession and layoffs mean many will have to head back to the office – at least for now.

How the balance has shifted

Just three years ago, a full-time employee working remotely even occasionally was a special privilege, reserved for workers in very specific special arrangements.

The pandemic, however, sent much of the workforce home, particularly in knowledge-work sectors. For many employees, virtual work enabled them to forge new, productive working habits, and establish a greater work-life balance once they were freed up from daily commutes and nine-to-five office presenteeism.

In this shift, flexibility quickly became the most sought-after job perk. Amid record vacancies and quit rates, many employers dangled the option of remote work to job candidates and existing employees alike.

Data shows worker retention largely drove this widespread remote-work adoption: according to a July 2022 study of 13,382 global workers by consulting firm McKinsey & Company, 40% said workplace flexibility was a top motivator in whether they stayed in a role, barely behind salary (41%), with 26% saying a lack of flexibility being a major factor in why they quit their last role.

Indeed, some companies, like Airbnb, made good on these promises immediately – they instituted permanent remote work arrangements. Many other employers implemented at least some remote work, putting in place hybrid-working policies.

Labour market conditions meant bosses had little leverage to reverse these policies, even when offices began to open again; businesses that demanded workers back to the office were met with staff backlash or even quits. At a time of huge economic growth, employers had little choice but to build flexibility into their organisations.

“By inclination, executives want their people in the office, more than they do remote,” says Charley Cooper, the chief communications officer at enterprise-technology provider and blockchain-software company R3, based in New York City. “However, they were unable to enforce that during the peak of the pandemic hiring boom: the competition for talent meant if you made your employees come back to the office, they’d call your rival and take a job there.”

Should an employee dislike a new work arrangement, layoffs across the board mean they’ll likely be much less confident that another role is waiting for them – Charley Cooper

But as the labour market has turned, for some companies, some of these remote arrangements no longer stand. The tech slowdown and looming economic instability have meant retention is no longer a top priority – particularly amid job cuts.

Employers now have greater leverage in demanding their workers back to the office. “Should an employee dislike a new work arrangement, layoffs across the board mean they’ll likely be much less confident that another role is waiting for them,” says Cooper.

This is even the case as the demand for flexibility remains strong among workers. A December 2022 survey of 10,992 US employees shows that 30.6% want to work from home full-time. And the option for flexibility has even changed workers lives: some have augmented their hours to become non-linear, or developed patterns to carve out better work-life balance based on their virtual-working routines. Some workers have even moved away from commuting distance to the office.

Yet “tech firms have begun to slowly get tougher on enforcing mandates to try and increase office days”, explains Nicholas Bloom, professor of economics at Stanford University. “The layoffs will have definitely accelerated this: employees worrying about layoffs are now much more likely to come to the office on days they’re supposed to be in.”

Explaining return-to-office mandates

Aware that employees may be unhappy with the changes, some have veered away from calling the changes a ‘return to office’, instead branding them as a move towards “flexible, intentional working”, for example.

Yet, as the worker-favourable labour market continues to sour, this kind of gentle corporate messaging has become less important, as it becomes easier to replace an employee than it was at the height of the hiring crisis. Workers know this too, says Cooper. It means if their boss asks them to return to the office five days a week – no matter how managers label the directive – employees will have to comply, or risk losing their jobs.

Executives that demand workers back to the office may wind up losing their top talent. But, for management at least, the benefits seemingly outweigh the risks.

Some companies are willing to spend more time and resources getting employees back in the workplace more regularly – or find new ones that will. “It shows how much they value that in-person interaction and leadership style,” says Bryan Hancock, partner at McKinsey, based in Washington, DC. “In a sense, they’ve seen that some elements have been lost during Covid, and this is a way of getting some of that back.”

Beyond a desire for workers in seat for business reasons, some experts, including Wendy Hamilton, CEO at TechSmith Corporation, based in Michigan, US, suspect some bosses are reneging on flexibility as a way to covertly downsize after a period of over-hiring, too.

She believes employees who want to remain remote can show themselves out the virtual door – and, in some instances, employers won’t move to replace them.

Where it leaves workers

How the current swathe of return-to-office mandates affect the workforce writ large will likely depend on their success – and whether wider companies jump on the trend.

Cooper says the leading corporations across sectors are the ones who are demanding their workers back to the office the most, with smaller firms choosing to delay their decision. “You have the likes of JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs currently issuing deadlines, with other banks waiting to see what happens next, ‘If it succeeds, we’ll follow suit’.” In other words, the widespread adoption of return-to-office may normalise the end of the remote-work privilege.

However, even though these moves point to a shift away from fully-remote working patterns that peaked during the pandemic, “we’ll still likely end up at a higher share of remote working than before the pandemic”, says Hancock, as many of the companies recalling workers are still settling for three or four days in the office, as opposed to one or two, leaving at least a little remote work in place.

For now, macroeconomic factors mean that power is shifting away from workers: bosses now have agency in determining the next phase in the new world of work – and how often workers need to be in the office. If companies are willing to diminish, or completely eliminate, the flexible work that so many employees desire, it could spell the end for the worker power that defined the pandemic era.

While there’s not yet proof of a definitive trend pointing to a mass return to office for all workers, it’s not an impossibility, say some experts. “It’ll be over the course of the year, and forcing people back that we’ll all get a sense of whether productivity remains the same,” says Cooper, “and if companies really are more innovative when people work together in the same room.”

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

[ad_2]

Source link