[ad_1]

An unearthed cache of century-old photographs of a South African choir that had performed in Victorian Britain inspired a choreographer to reimagine what they went through as they toured the country.

Gregory Maqoma remembers going into his favourite space in the Apartheid Museum in South Africa’s main city, Johannesburg, five years ago.

It is a room in the round – with only one way in and out and gently curving walls that, he says, fills him with a sense of serenity and privacy.

The South African choreographer was drawn to the centre of the room by the sound of music and singing voices.

It was a sound installation by composers Thuthuka Sibisi and Philip Miller. They had worked with contemporary singers to reinterpret the performances of a 19th Century South African choir – based on songs listed on a surviving concert programme.

Captivated, Maqoma danced for 40 minutes – before he sensed another presence.

Looking down on him from around the room was a series of 20 photographic portraits of the members of the original choir, a group of young, black intellectuals who had toured England, Scotland and Ireland between 1891 and 1893 under the name of the African Native Choir.

“The intensity of how they were looking at me dancing made me start asking questions about ‘the gaze’ – how we are looking at each other and how people had looked at them at the time,” Maqoma says.

The photographs were taken by the London Stereoscopic Company, but they had laid unseen for over 100 years until 2014.

Autograph ABP – a London gallery that was researching the presence of black people in Britain before 1948 – unearthed the original glass plates wrapped in parchment paper in the Hulton Archives in London, now part of Getty Images.

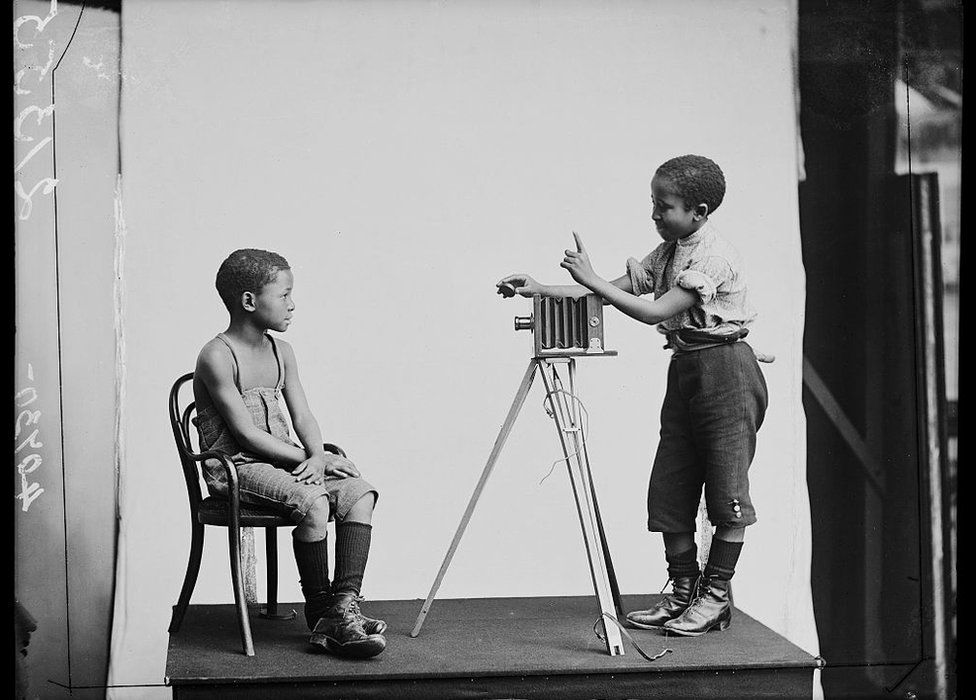

There are more than 30 individual and group photographs of 16 choir members – seven women and seven men and two young choir boys.

Some images are expressive close-ups, some are playful – especially with the two young boys, Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe.

In one photo one of them relaxes, smiling, in front of the camera while the other stands behind it posing as the photographer.

But most of the photographs conform to Victorian stereotypes and expectations of people from Africa as “traditional” and “tribal”.

In one group photo, the choir are wrapped in animal skins, some with feather and bead headdresses.

And they have been seated in front of a tiger skin – despite there being no tigers anywhere in Africa and despite the choir members coming from urban areas such as Kimberley, and having been educated at missions including Lovedale in what is now the Eastern Cape.

“That tiger – well, that was just very odd,” Maqoma says.

His first encounter with the portraits also sparked a feeling in him that he was the “carrier of their spirits”.

“I wanted to answer so many questions: what happened to them travelling from South Africa by boat to arrive in the UK, in a country of the coloniser? How were they received?”

And so he went to composer Sibisi, and together they created a piece of work that reimagines the physical and spiritual journey of the African Choir.

Broken Chord is a 60-minute production, in which Maqoma is the central dancer alongside four soloists and a chorus.

It is a highly physical, deeply emotional performance, which combines Xhosa and contemporary dance styles, musical harmonies from South Africa and Western classical traditions, English and Xhosa languages along with atmospheric sounds and smells.

On the face of it, the trip of the African Choir was a triumph.

One British newspaper, the Standard, described it in 1891 as a “unique performance, and the audience followed the various items in the programme, some of which were sung in the native tongue, and others in almost faultless English, with warm tokens of interest and approval”.

Queen Victoria asked them to perform for her at Osborne House, the Royal residence on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England.

But years later – in a memoir of her life, including describing her work in medicine and nursing – one of the singers, Katie Manye, recalled how after that performance on 24 July, a granddaughter, accompanying the Queen, made a comment using a derogatory term about how she did not like people from Africa.

It was not an isolated experience.

Manye also recounts how the choir members objected to the use of another derogatory and contemptuous word to describe them.

Her memoir says the tour manager Mr Howells ignored their objections saying: “That’s what you are – the English… will be curious to hear you sing.”

Overall, the trip was difficult.

They often had to travel from town to town to perform, and dislikes and conflicts between each other emerged.

There was also a personal tragedy. One of the women became pregnant – and no-one else knew until the body of her stillborn baby was found in her trunk.

The choir was not paid the money they had been promised – and in the end the singers were abandoned by the managers and left penniless in a London hotel.

They were able to return to South Africa because a missionary society raised funds for them.

Their story of homesickness, discrimination – but also defiance, determination and dignity – is also a much broader story.

“Broken Chord kind of morphed from being just the story of the choir. It became about the resonance to the now, to what we are navigating today – around race, around migration, around intolerance, around the things that we are always struggling about,”Maqoma says.

Maqoma embraced dance because of those kinds of struggles – specifically the traumatic oppression of South Africa’s apartheid system, which legalised racial discrimination.

He was “surrounded by dust and smoke and police sirens” during the 1980s.

He grew up close to a hostel that housed migrant workers from different parts of South Africa who worked in factories and mines.

At weekends, they would hold traditional dance competitions – and Maqoma would be there among the cheering onlookers.

“I was fascinated by just the sheer beauty of movement. How it made me forget about the conditions that I was living in, the heaviness of what the country was going through.”

Maqoma also recalls seeing Michael Jackson on a small black-and-white television in his Soweto home – awed by the power he commanded by the small gesture of slowly removing his signature glove.

In 1990, when still a teenager, Maqoma got his first big break and he went on to dance to huge acclaim all over the world.

He also founded Vuyani Dance Theatre – Vuyani, which means joy, being his middle name.

Some 132 years later Maqoma has followed in the footsteps of the African Choir – coming to London to perform Broken Chord at one of the city’s oldest theatres, Sadlers’ Wells, in what is his last dancing tour, which also takes in Paris, Amsterdam and some cities in the US.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

[ad_2]

Source link